A stumble in Australia that dynamited confidence in AI

Two months ago a episode in Australia set off alarms about the risks of applying generative artificial intelligence (AI) without proper human supervision. Deloitte Australia had been hired in December 2024 by the Department of Employment and Labour Relations (DEWR) to evaluate an automated welfare control system. It was a sensitive commission, carried out after the scandal "Robodebt" (undue charges to social beneficiaries) that had alerted the country, which increased the importance of the resulting report. The final product was a 237-page report delivered in July 2025, which initially did not reveal the use of AI in its preparation at all.

The report seemed comprehensive and technical, until late August 2025 when a legal researcher at the University of Sydney, Dr. Chris Rudge, discovered something disturbing upon reading it. One of the footnotes quoted his colleague, Professor Lisa Burton Crawford, attributing to him a nonexistent book on constitutional law – a work that simply could not exist in his field of expertise. According to Rudge, I instantly knew that I had been hallucinated by AI or it was the best kept secret in the world, because I had never heard of the book and it sounded absurd . This initial anomaly led to a deeper analysis of the document, uncovering approximately 20 manufactured bugs in total. Among them were False academic references (made-up books and articles attributed to real experts) and Miscitations , such as a court case cited with references that did not correspond and a false quote attributed to a federal judge (misspelled name and with words she never spoke). Even more worryingly, the report dealt with that case ( Amato vs Commonwealth ) as if there had been a firm trial, when in fact it ended in a consent agreement – a mistake that denoted Basic legal misunderstanding by the authors of the document.

Aware of the seriousness, Rudge decided to alert the press. It is one thing to incorrectly cite academics or impute non-existent works, but it is quite another to incorrectly quote – and therefore misrepresent – the law in a government report , he explained, stressing that misinforming the Executive about jurisprudence was a very serious matter. Their findings were published by the Australian Financial Review in late August, sparking uncomfortable questions about how one of the "Big Four" of the consultancy was able to deliver a report with errors that a freshman I would know how to avoid.

Rushed Corrections, Partial Refund, and Painful Lessons

Deloitte's response was not long in coming, although it tried to go under the radar. On September 26, 2025, the firm quietly replaced the original report on the official website with a revised version. In this update, they removed more than a dozen fictitious references and corrected false court citations attributed to the federal judge. They also suppressed mentions of non-existent books and, for the first time , included an explanatory note indicating that in the preparation of the document a toolchain based on Azure OpenAI (GPT-4o) had been used . This confession that AI was part of the process exposed the initial lack of transparency. In the new introduction, Deloitte assured that The updates made do not impact or affect in any way the substantive content, findings, and recommendations of the report , acknowledging that they used GPT-4 during the initial draft but claiming that a later "Human review refined the content" . The firm thus maintained that the conclusions remained fully valid.

However, the way Deloitte corrected the report raised new doubts about the rigor of the process. When journalists asked for examples of the amended references, it was found that The new sources also did not support the original claims , suggesting that the firm attempted to correct the errors by asking the AI again for "real" references for the same claims. In other words, the traceability It remained scarce: the claims in the report were not anchored in evidence, but in machine-made constructions without a solid documentary basis.

The incident caused financial and reputational damage in October 2025. To contain it, Deloitte Australia agreed with the government to Partial Contract Refund . Initially, it was proposed to return the final outstanding payment, and on October 20 the exact amount was confirmed: A$97,000 (about US$63,000), approximately 22% of the total contracted . Although Deloitte went on to state that The substance of the review is maintained and that there were no changes in the recommendations, the gesture of reimbursement implied a tacit admission of responsibility. From the government side, it was stated that "Some footnotes and references were incorrect" in the report, but that the main content was still valid – a diplomatic way of acknowledging mistakes without inflaming the issue. Still, the episode prompted the DEWR to announce that future consulting contracts will include stricter clauses on the use of AI , to prevent similar situations. On the political front, Senator Barbara Pocock of the Green Party demanded that Deloitte 100% refund of the AUD 440,000, regretting that the firm had misused AI: misquoted a judge, used non-existent references. The Kinds of Things a College Freshman Would Be in Serious Trouble For . Critical voices comparing an elite consultant to a rookie student reflected the reputational blow. Affected academics, such as Professor Burton Crawford, were also concerned about seeing research falsely attributed to their names.

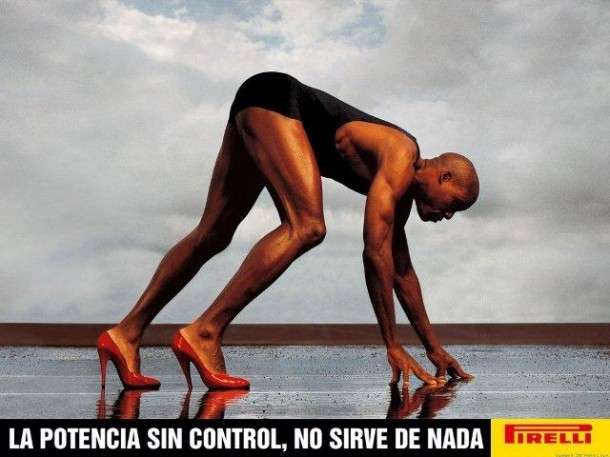

The final paradox came a few weeks later: the In the month in which Deloitte was facing this stumble with AI, it announced with great fanfare the massive deployment of another AI tool (Claude, from Anthropic) for its 500,000 employees globally . This contradiction – acknowledging serious flaws and simultaneously doubling down on AI – perfectly captured the moment we live in. Enterprise adoption of artificial intelligence is advancing at a breakneck pace, sometimes faster than adequate safeguards are in place , driven by competitive pressure and fear of being left behind. The Deloitte case, far from being an isolated scandal for public enjoyment, should be understood as An early warning sign about the systemic risks of using AI without proper controls. A mistake of hundreds of thousands of dollars – and the associated reputational damage – could have been have been completely avoided with the right approach and tools . Below, we draw the strategic lessons from this incident and explore concrete solutions so that history does not repeat itself.

The systemic risk of adopting AI without guarantees

What happened in Australia has resonated globally because it exposes a latent risk: the adoption of generative AI without proper safeguards is not just a problem for a consulting firm, but a systemic danger . It is becoming increasingly clear that, in sectors such as strategic consulting, public policy-making, or any regulated field, relying on AI models without robust human control can lead to catastrophic errors and ill-informed decisions.

Why exactly did Deloitte's "stumble" occur? The causes are both technological and organizational. On a technical level, the flawed report illustrates the phenomenon of AI hallucinations : Current language models, no matter how advanced they are, sometimes generate content that sounds plausible but is completely made up. This happens because a large generative model (LLM) is not a truth machine, but a machine for calculating probabilities ; It predicts words based on statistical patterns of its training, not on a proven understanding of reality. You can write very convincing sentences – even citations and references with impeccable academic formatting – but he is not aware of the veracity of those contents. As experts explain, these systems They can create plausible-sounding content without real sources or factual basis . And, unless they are complemented by specific mechanisms, they do not verify whether the sources mentioned actually exist . In fact, the more they've read actual academic texts, the more they are able to mimic their style and Fabricate credible quotes , which is a dangerous double-edged sword. In the Deloitte report, the AI simply generated references in the expected format because Learned of thousands of authentic reports, without distinguishing between the real and the fictitious.

At the organizational level, the case reflects shortcomings in quality control processes and in the culture of AI adoption. Large consulting firms operate in a very competitive market, with pressure to deliver faster and at lower cost . The temptation to turn to tools such as ChatGPT or similar to speed up the writing of extensive reports is understandable. Deloitte, by involving GPT-4 in the draft phase, was likely looking for those efficiencies. The problem is that, by focusing on speed and convenience, bypassed the checks needed to ensure accuracy . The basic errors detected – such as attributing to a judge phrases that he never said – indicate that the Human review was insufficient or not very senior . Even after the correction, the Lack of traceability : not even the consultants themselves could back up certain claims with real sources, because originally there were none . In addition, the firm failed to communicate the use of AI to the customer initially , a decision that deprived the DEWR of the opportunity to require additional guarantees or to analyse the outcome more carefully from the outset. This lack of communication breached good practices and undermined trust when everything came to light.

The systemic risk, therefore, is that a growing number of organizations incorporate generative AI into critical tasks without adapting their internal processes . If a company of Deloitte's caliber fell into this error, others may be doing so as well. In fact, we have already seen similar cases in different areas: in May 2023, two lawyers in New York were judicially sanctioned after filing a legal brief full of case citations Nonexistent created by ChatGPT. In the financial sector, this Deloitte incident is remembered as a wake-up call whereas it stresses that AI is not a truth-revealer; It's a tool designed to give answers that fit your questions. In other words, the machine will give you some answer –coherent in form– to any question, but it does not guarantee that it is correct in substance. If professionals forget this and place blind trust in the supposed intelligence of AI , the consequences can be serious. The constant narrative of how "smart" AI is can lead us to to rely excessively on it, even unconsciously, and to depend more than it should .

The public and regulated sectors face an added risk: Erosion of trust . In the Australian case, the failed report concerned a Automated social welfare system , already delicate after the previous scandal. A report with fabricated legal citations could have led to poorly calibrated public policies or to maintain flaws in a system that penalizes vulnerable citizens. Failures of this type can misinforming decisions that impact millions of people and undermining public trust in automated government systems . When citizens learn that a government report has "beginner's" errors generated by AI, the damage transcends the consulting firm: doubts are sown about the quality of the policy-making process in general and about the reliability of the technology used by institutions.

Fortunately, this episode is also generating interesting debate and corrective measures. The Australian government, as we saw, announced specific contractual clauses for future consulting work involving AI. And at the international level, they are already outlined Best practices to avoid another Deloitte-gate . A number of experts and agencies are proposing, inter alia, the following concrete measures:

- Strict clauses on the use of AI in contracts : Customers should clearly stipulate when and how AI can be used on a commission, demanding full transparency and human review certifications before delivery.

- Source auditing and traceability : every statement in a report must be able to be traced back to its source with Human-verifiable sources Qualified. This involves keeping records of the prompts and AI outputs for auditing.

- Cross-cutting regulatory frameworks : it is anticipated that governments and professional associations will establish guidelines on the use of AI in professional services (consulting, auditing, legal, etc.), to homogenize standards of quality and responsibility at an international level.

- AI Training for Staff : human teams must train in AI literacy , being able to detect hallucinations or implausible references and to understand the limitations of the model. AI cannot be left in the hands of untrained users.

- Ethical risk management : in High risk (public policy, social welfare, regulatory, legal), must be applied additional safeguards when AI is involved , such as independent inspections, expert double verification, or pilot testing before conclusions are implemented.

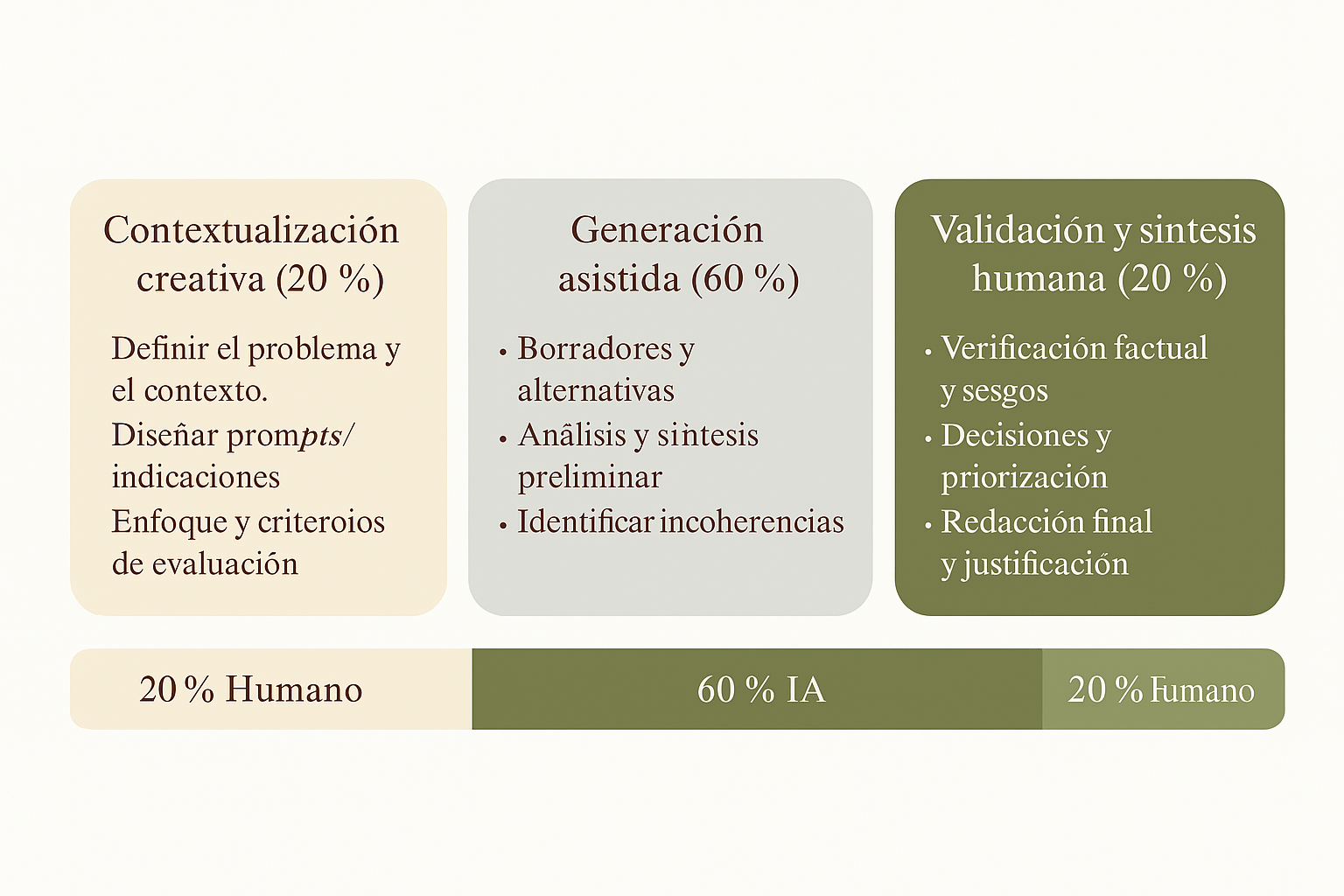

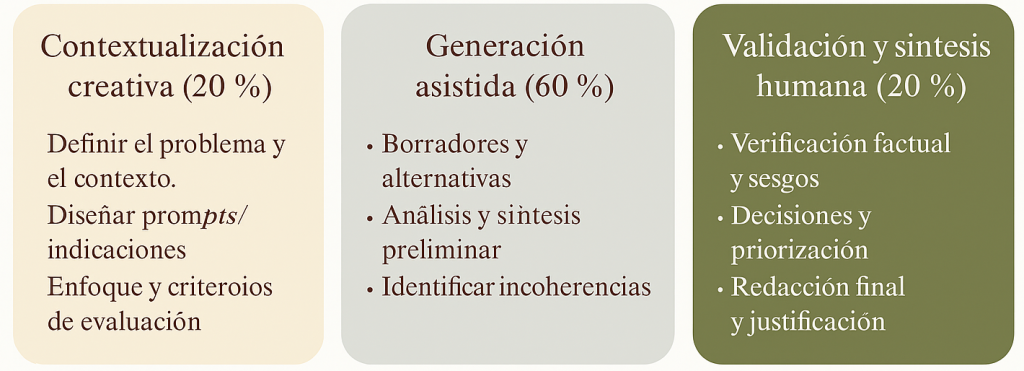

Implementing these measures requires important changes in the way we work, but they are increasingly necessary. In essence, they all point to one central idea: Keeping the human being "in the loop" , controlling and validating what AI proposes. It is not a question of slowing down innovation, but of integrating it responsibly. And this is precisely where an approach that we at Proportione have been developing in projects with clients and that we also apply in training environments becomes relevant: the 20–60–20 model of Human–AI–Human collaboration . Let's take a look at what it is and why it can be the key to leveraging AI without compromising quality or ethics.

The 20–60–20 model: Human–AI–Human collaboration with rigor and traceability

At Proportione we conceive the Model "20–60–20" as a response to the challenges we have shown. This model, formulated by Javier Cuervo , divides any AI-assisted intellectual task into Three phases with indicative contribution percentages :

- Initial 20% contextualization and human design : At the beginning, the person defines the problem, the context, the objectives and the objectives of the project. Quality criteria that is expected. It is a phase of Critical framing : Reliable data is collected, relevant reference sources are selected, and clear instructions for AI are written. In simple terms, here the human sets the course and sets the limits.

- 60% AI-assisted generation : Next, the AI generates drafts, analyses or content based on the indications given. This is the phase of productive acceleration. The machine proposes text, identifies patterns or even suggests references, always following the initial human guidelines. AI's contribution can be invaluable in gaining speed and exploring approaches, but it's critical to assume that What is produced in this section is a draft susceptible to errors .

- 20% final validation and human review : Finally, the person performs a makes an exhaustive critique of the entire output of AI . This is the indispensable quality filter: every piece of information is checked, all citations and references are checked, tone and consistency are corrected, and the result is compared with reality and with the initial objectives. This phase may involve consulting original sources, adjusting nuances that AI does not capture (e.g., legal or cultural considerations), and ensuring that the final product meet ethical and rigorous standards Expected. Only when the human review gives its approval is the work considered finished.

This 20–60–20 approach balances the power of AI with human judgment , in a structured way. In practice, it means that the work Always start and Always finish with human intervention, leaving AI embedded in the middle as a support tool, not as an autonomous agent. We have already applied it in different contexts. For example, in a recent business training project we combined role-play of corporate crises with the 20–60–20 model (20% creative contextualization, 60% generation with ChatGPT and 20% human validation), getting participants to significantly improve the coherence of their analyses without reducing critical demand. The essence of the methodology is to transform AI from being an opaque oracle to turning it into a Intellectual co-pilot under human supervision. This promotes skills of prompt engineering , ethical judgment and strategic analysis, because it forces the user to actively interact with the tool, formulating good instructions and then auditing the results.

Use in consulting, the 20–60–20 model provides Rigor and traceability precisely where AI alone falters. During the initial 20%, the human team can Prevent many hallucinations by providing specific context and sources to the AI (e.g. by uploading verified reference documents or narrowing queries to well-defined areas). In the middle 60%, productivity skyrockets: AI makes it possible to quickly generate text sections, summaries, or comparison charts, freeing consultants from mechanical work and allowing them to iterate multiple ideas in a short time. Recent studies indicate that generative AI well used can increase knowledge work productivity by around 14% on average , with especially noticeable improvements in less experienced professionals. That push for efficiency is real – Deloitte was looking for it, no doubt – but It only materializes safely if it is accompanied by discipline in the verification of results . That's where the last 20% comes in.

The final critical phase ensures that nothing generated by AI reaches the customer without first passing through the sieve of human intelligence. Each figure, each bibliographic or legal citation will be contrasted with reliable sources; any statement must be supported or qualified as appropriate. This is a direct antidote to lack of traceability and invented references : If the AI suggested a data without a source, the consultant will detect it and replace it with a verified piece of data or eliminate it altogether. In this model, No dubious sentence survives the final revision . Traceability is ensured because the final deliverable is accompanied by a trace from real sources that the human team itself has validated. Likewise, the documentation of the process is emphasized: save the prompts used, intermediate versions, and human editing decisions, so that in the event of any customer questions or future audits, it can be demonstrated what the AI did and what the human corrected – exactly the type of record that was missing in the Deloitte case.

20–60–20 encourages a Healthy human-AI collaboration culture . It is not about rivalry or substitution, but about adding capabilities. As a result, the professional develops a new competence: he knows how far to trust the machine and where to start the process. reasonable doubt . In our projects we have seen young consultants who, following this model, quickly learn not to Copy-paste Not only do the chatbot's answers, but rather use them as a basis that they then enrich or correct with criteria. AI is no longer an all-powerful black box and becomes a Structured Assistant , always under the control of the human expert.

The Senior Criterion: The Final 20% AI Can't Replace

A fundamental aspect of the 20–60–20 model – and, we would say, of any sensible AI adoption strategy – is the The irreplaceable role of senior human judgment in the last stage of the process . The experience of the Deloitte case is clear: if a professional with a deep domain of the subject (for example, a senior lawyer specializing in administrative and constitutional law) had intervened with sufficient rigor in the final phase of the review, it is very possible that such flagrant errors would not have gone unnoticed. Someone with the smell and accumulated knowledge that seniority gives would have immediately questioned unusual quotes or unknown references, in the same way that Dr. Rudge did when reviewing the report – with the difference that Rudge arrived at the When the damage was already done , not before.

The Last mile AI can't do it for us. In high-level consulting, as in auditing, medicine, or law, expert judgment remains the safety net. No matter how advanced the generative model is, it lacks full contextual understanding: it does not know the fine print of the laws, nor the political implications of a certain recommendation, nor the organizational values that nuance a strategy. An experienced partner-consultant or project manager does have that contextual and ethical sense , and must apply it conscientiously in the final 20%. It is the difference between a document that is simply Well written and a document correct and relevant . At its core, generative AI equates to a very diligent junior analyst or intern: it produces a lot and very quickly, but Requires supervision . In the aftermath of the Australian incident, firms must train staff not only in the effective use of AI, but also in its ethical use and in maintaining quality control, treating AI results as if they were prepared by an intern or new employee. What comes out of ChatGPT must face the criterion of senior Just as the draft report of a novice consultant goes through the adjustments and corrections of the manager or partner in charge.

In our experience, the input of senior professionals in the final review adds value in three key dimensions:

- Technical quality : They detect inconsistencies, conceptual errors, or important omissions that the AI (or an inexperienced human) would not perceive. In the Deloitte case, a senior legal expert reportedly warned that the case Amato vs Commonwealth it did not have a publishable verdict and that citing it as legal support was inadmissible. Similarly, a senior in public policy would have questioned claims without solid empirical support.

- Ethics and reputation : A manager with ethical criteria and corporate vision values not only what says the report but how he says it and what implications it has. For example, it could detect bias in AI-generated language, make sure recommendations don't violate equity principles, or simply decide No, we cannot deliver this to the customer if something seems doubtful. Ultimately, this filter protects the client relationship and the firm's reputation.

- Contextual adaptation : Seniority involves understanding the client's environment and the circumstances of the project. In the final phase, the expert sets the tone, prioritizes the findings that are truly relevant to that client, and contextualizes the recommendations. AI can produce standard text, but the senior human turns it into a tailor-made strategic message.

It should be noted that senior human intervention is not a luxury, it is a Professional obligation . Codes of good practice say this because the responsibility continues to fall on the professional who uses AI, that is, delegating to the machine does not exempt from blame if something goes wrong. Consultants must Appropriate the work, verify the results, and apply their judgment instead of copying and pasting what the system produces . The report is signed by the consulting firm, not the algorithm; Therefore, a partner should be able to defend each paragraph in front of the client. If there are errors, they are our Errors. The goal is not to avoid AI mistakes, it's to make sure we're smart enough to spot them as final decision-makers. That is where experience and human judgment demonstrate their value: in recognize what AI may have done wrong, and correct it before it transcends .

Far from making professionals obsolete, the irruption of AI has Raised the bar for seniority . Now is when we most need leaders with good judgment, capable of integrating cutting-edge technology into their teams without sacrificing critical control . AI can take care of the first layer of work, but the ultimate layer of quality and strategic sense is still human territory. It's the best time for good strategists.

Transferring knowledge, not just technology

Another strategic lesson from this case is that Technology transfer without parallel knowledge transfer is irresponsible and unsustainable . We are experiencing a boom of AI tools entering organizations, but buying or implementing the latest platform is not enough: you have to make sure that people know how to use it judiciously. At Deloitte Australia, for example, GPT-4 was used through Azure OpenAI – a cutting-edge technology – but it is worth asking whether the consulting team was properly trained to use it. Did they understand their limitations, did they know how to verify their answers, did they have clear guidelines for use? Judging by the result (and by the need to patch up the report by asking for new references to AI itself), it is clear that Lack of internal training in the responsible handling of the tool.

This gap between technology and knowledge can occur both within consulting firms and between consultants and clients. If a consulting firm delivers AI-supported work without disclosing it, it does not provide the client with the opportunity to learn about the process or prepare to give continuity to that methodology. On the other hand, when an organization adopts an AI solution on the recommendation of third parties but it does not train its employees In the new dynamics, you are buying a ticket to future problems. Customers must master the tools they adopt , or at least understand their risks, otherwise they will be blindly dependent on the third-party provider. That is why in each Proportione project we emphasize not only implementing the technical solution, but also accompanying it with group work, best practice manuals and supervised testing periods. Introducing AI into an organization involves Change Management : new workflows, new skills to develop and a culture of quality control.

In the case at hand, in the wake of the scandal, the Australian government updated its contracts to require consultants not only to give advance notice if they use AI, but also to preserve detailed records of interactions with AI (prompts and results) and ensuring that agency data is not unduly or internationally exposed. These are measures aimed at ensuring that the process knowledge remains accessible to the customer . If the DEWR had received from the beginning along with the report an annex with all the messages sent to the model and the suggested sources, its own analysts could have detected inconsistencies. This forced transparency in the use of AI is a way of transferring know-how: the client can audit and, therefore, learn where the AI fits (and where it fails) in the task at hand.

Returning to the field of professional firms, the watchword must be Train before automating . This ranges from training staff on AI fundamentals (what a language model is, what it can and can't do) to training them in practical skills: how to write good prompts for AI, how to verify responses with independent sources, how to identify a potential hallucination, how to avoid bias, etc. There are already projects to improve the Data Literacy and AI of their workforces, in the same way that a few years ago training in general digital skills was promoted. Incorporating AI without this training reinforcement is irresponsible. Not only the quality of the product is at risk, but also the employees' trust in the tool. If professionals feel that AI is a black box that can make them look bad, or that management implements it without giving them guidance, understandable resistance or, worse, misuses, will arise. On the other hand, when adopting with pedagogy, the staff understands that AI is a strategic ally under its control , and uses it more effectively and ethically.

Every euro invested in training and clarification of AI processes will pay off in error prevention and productivity improvement. Technology, no matter how brilliant it is, does not guarantee results if people do not know how to pilot it. In this sense, Transferring knowledge (methodologies, criteria, experiences) is even more important than transferring the latest version of the software. The optimal balance is inseparable: Technology + Knowledge , or there is no true digital transformation.

Conclusion: in the age of AI it is time to put sense and responsibility

The "Deloitte Australia case" is not a simple local mishap or a weapon against the consultancy; it is, above all, a symptom and a learning for all organizations immersed in the AI race. It reminds us that incorporating generative AI into our work comes with huge opportunities, but also risks that need to be actively managed. We can – and must – draw a conclusion from this story: it is not enough to deploy AI, criteria must be formed to use it meaningfully .

Proportione's 20–60–20 model of Human–AI–Human collaboration is one of the concrete ways to achieve this balance. He assures that the AI-augmented creativity it is not to the detriment of the rigor or ethics , but quite the opposite: it boosts productivity while reinforcing human control at critical points. Ultimately, methods like this turn what could be a leap into a technological vacuum into a Controlled and strategic leap . AI is integrated, yes, but without letting go of the human rudder.

Organizations that aspire to lead in the AI era would do well to Adopt proactive safeguards . This means establishing clear internal protocols, investing in ongoing training, and fostering a culture where seniority weighs more than ever . Paradoxically, the more advanced the tools, the more valuable human experience and judgment are in directing them. It is not a question of slowing down innovation, but of Innovate wisely . Because the question is no longer yes we will use AI – that is a fait accompli – but how we will. And in that "how" is where it will be defined who achieves good results without compromising trust.

Every project, every report, every AI-assisted decision must be conceived under the premise of the double technical and human guarantee. Let's review our processes today, add that 20% expert reflection at the end and at the beginning, and use AI in the middle 60% with our eyes wide open. To those who lead teams, set an example by combining curiosity about the tool with seriousness in supervision. To those who are beginning to rely on ChatGPT or similar in their daily work, demand even more in the verification of what is produced. AI can speed up our pace, but the path is marked by human judgment . In the union of both lies the future of an efficient and reliable consultancy – and in general of professional management.

It's not enough to adopt AI: you have to know how to drive it. The difference between a disaster and a success story will depend, to a large extent, on maintaining that intelligent balance between technological innovation and human wisdom. It's in our hands – not the machine's – to ensure that the promise of AI is fulfilled without betraying the trust customers have placed in us.